This is part of a series discussing The Theory of the Leisure Class, by Thorstein Veblen. His fourth chapter is Conspicuous Consumption.

Leisure and consumption are accepted as equivalent in demonstrating the possession of wealth. Choosing between them as a matter of advertising one’s wealth depends upon the stage of economic development as to which will most ‘effectively reach the persons whose convictions it is desired to affect’. So long as the community or social group is small, they are equally effective. However, consumption wins over leisure as community size increases, as it becomes more difficult to display one’s exquisite manners or knowledge of archaic languages, for example. Then again, Veblen didn’t live in the time of blogging, did he? He does, however talk about the formation of neighbourhoods in which the occupants of nearby houses have little contact, often a feature of life today, sadly.

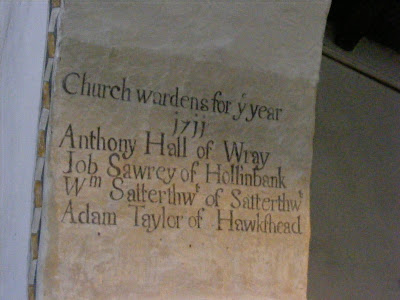

With a more mobile society people unknown to one another come into contact: at churches, theatres, ballrooms, hotels, parks, shops. These are Victorian examples, to which one could add work, gyms, school gatherings, sporting events, etc. Without more intimate knowledge, people can only judge one another based on a display of goods and perhaps breeding (which I now understand means training, not bloodlines) during a relatively short period of observation. The only unfailing way to impress these transient observers is by showing evidence of pecuniary strength. Thus, conspicuous consumption is more useful in this changing society.

Veblen contrasts urban vs. rural living in this respect. Urban dwellers spend more of their income on conspicuous consumption and it’s more important that they do so, so he says they habitually ‘live hand-to-mouth’ more than rural inhabitants. The latter are notoriously less ‘modish in their dress’ and ‘less urbane in their manners’ in spite of an equal family income. This is not because they care less, but because urban dwellers are more ‘provoked to this line of evidence’ and the effect is more transient, so that city dwellers have a greater struggle to outdo one another. The need to conform to this higher standard becomes mandatory. The standard of ‘decency’ is higher, class for class, and so on pain of losing caste, city dwellers spend more and save less.

In expounding about city life, Veblen singles out the drinking and smoking habits of some of the lower classes, particularly journeymen printers. He says that because their printing skills allow them to be so mobile and they readily move to a new place to improve their circumstances, they are constantly thrown in with new acquaintances. In order to be accepted in the new group and well thought of leads inevitably to dissipation, I suppose from buying too many rounds at the pub to prove one is reputable and able to pay.

However, in the country, one can be known - through neighbourhood gossip - to have considerable savings or a comfortable home and so this outward display is not as necessary. This is the advantage of everyone knowing everyone else’s business. So, we should all get to gossiping about our neighbours, to help them build their savings!

The next post will attempt to address the idea of waste vs. workmanship. This latter term is a difficult concept for me, but we'll see how it goes.